Imagine that you are tasked to build an entire private cloud infrastructure from the ground up. You have a limited budget, a small but dedicated team, and are asked to pull off a miracle.

A few years ago, you’d build an infrastructure with applications running in virtual machines, with some bare-metal machines for legacy applications. As infrastructure has evolved, virtual machines (VMs) enabled greater levels of efficiency and agility, but VMs alone don’t completely meet the needs of an agile approach to application deployment. They continue to serve as a foundation for running many applications, but increasingly, developers are looking toward the emerging trend of containers for leading-edge application development and deployment because containers offer increased levels of agility and efficiency.

Container technologies like Docker and Kubernetes are becoming the leading standards for building containerized applications. They help free organizations from complexity that limits development agility. Containers, container infrastructure, and container deployment technologies have proven themselves to be very powerful abstractions that can be applied to a number of different use cases. Using something like Kubernetes, an organization can deliver a cloud that solely uses containers for application delivery.

But a leading-edge private cloud isn’t just about containers, and containers aren’t appropriate for all workloads and use cases. Today, most private cloud infrastructures need to encompass bare-metal machines for managing infrastructure, virtual machines for legacy applications, and containers for newer applications. The ability to support, manage and orchestrate all three approaches is the key to operational efficiency.

OpenStack is currently the best available option for building private clouds, with the ability to manage networking, storage and compute infrastructure, with support for virtual machines, bare-metal, and containers from one control plane. While Kubernetes is arguably the most popular container orchestrator and has changed application delivery, it depends on the availability of a solid cloud infrastructure, and OpenStack offers the most comprehensive open source infrastructure for hosting applications. OpenStack’s multi-tenant cloud infrastructure is a natural fit for Kubernetes, with several integration points, deployment solutions, and ability to federate across multiple clouds.

In this paper, we’re going to explore how containers work within OpenStack, examine various use cases, and provide an overview of open source projects, from OpenStack and elsewhere, that help make containers a technology that’s easily adopted and utilized.

There are three primary scenarios where containers and OpenStack intersect.

The first scenario, called infrastructure containers, allows operators to leverage containers in a way that improves cloud infrastructure deployment, management, and operation. In this scenario, containers are set up on a bare-metal infrastructure, and are allowed privileged access to host resources. This access allows them to take direct advantage of compute, networking, and storage resources that container runtimes are typically trying to hide from users. The containers isolate the often complex set of dependencies that each application depends on, while still allowing the infrastructure applications to directly manage and manipulate the underlying system resources. When the time comes to upgrade an service, the upgrade can be handled without changes in dependencies disrupting co-located services.

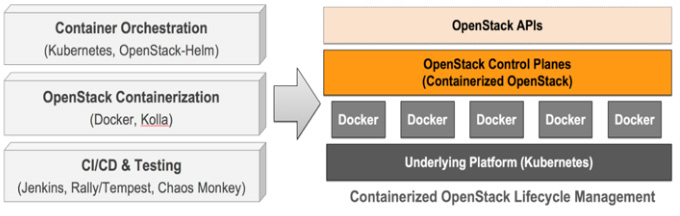

Modern versions of OpenStack have embraced this infrastructure container model, and it’s now normal to manage an entire lifecycle of an OpenStack deployment with a combination of orchestration tooling and containerized services. Infrastructure containers enable operators to use container orchestration technologies to solve many issues, particularly around rapidly iterating/upgrading existing software including OpenStack. Running OpenStack within containers helps operators to solve Day 2 challenges, including adding new components for services, upgrading versions of software quickly, and rapidly rolling updates across machines and data centers. This approach brings the agility of containers to the problem of OpenStack deployment and upgrades.

The second scenario is concerned with hosting containerized application frameworks on cloud infrastructure. These can include Container Orchestration Engines (COEs) like Docker Swarm and Kubernetes, or lighter-weight container-focused services and serverless application programming interfaces (APIs). Whether on bare-metal or VMs, the OpenStack community has worked to ensure that it’s possible to deliver containerized applications on a secure, tenant-isolated cloud host. This scenario is facilitated by drivers that allow projects like Kubernetes to directly take advantage of OpenStack APIs for storage, load-balancing, and identity. It also includes APIs for provisioning managed Kubernetes clusters and application containers on demand. With these capabilities, development teams can write new containerized applications and quickly provision Kubernetes clusters on OpenStack clouds. It’s a complete application lifecycle solution that gives them the resources needed to develop, test, and debug their code, with robust automation to deploy their applications into production.

In the final scenario, we consider the interactions between independent OpenStack and COE deployments, and in this paper particularly Kubernetes clusters. Consistency and interoperability of APIs across both OpenStack and Kubernetes clusters is the primary source of success for this scenario. For example, it’s possible for Kubernetes to directly attach to OpenStack Cinder hosted volumes, use OpenStack Keystone as an authorization and authentication backend, or connect to OpenStack Neutron as a network overlay with OpenStack Kuryr. Conversely, it’s possible for an OpenStack cloud to share the same network overlay as a Kubernetes cluster with Neutron drivers for projects like Calico. The third scenario is less focused on how a cloud service is hosted (be it Kubernetes or OpenStack), and more on how independent services interact.

As noted in the introduction, the deployment and management of OpenStack has changed significantly with the rise of containers, because containers unlock new approaches to managing infrastructure code. Previous management strategies required either the creation and maintenance of heavyweight golden machine images, or using brittle state-maintaining configuration-management systems. Each approach comes with complexities and restrictions. Adding to the degree of difficulty is the management of a collection of services that all require their own dependencies that change from release-to-release. Without some form of application isolation, solving for the dependencies becomes difficult if not impossible.

Infrastructure containers enable new OpenStack deployment projects to strike a balance between the two while elegantly solving the dependency problem. Using lightweight, independent, self-contained, and typically stateless application containers, a cloud operator gains tremendous flexibility when deploying a complex control plane. Combined with a container runtime and an orchestration engine, infrastructure containers make it possible to quickly deploy, maintain, and upgrade complex and highly available infrastructure.

In building an OpenStack cluster, there are several dimensions for choosing deployment technologies. An operator could choose Linux Containers (LXC) or Docker for their base containers, use pre-built or custom-built application containers, and select either traditional configuration-management systems for orchestration or a more modern approach like Kubernetes. Table 1 summarizes the existing OpenStack deployment projects and their underlying technologies.

Underlying each of these deployment systems are different approaches to building a set of containers for the OpenStack code and supporting services. The OpenStack Ansible (OSA) and Kolla projects provide their own project-hosted build systems, while LOCI focuses on building project application containers, without a specific orchestration system in mind. At a high level, the differences are:

At the foundation of every cloud, there exists a data center of bare-metal servers that host the infrastructure services. Even “serverless computing” is running software on a cloud on hardware in a data center. The problem of how to bootstrap hardware infrastructure is a critical problem that OpenStack software is uniquely qualified to address in a way that gives cloud-like qualities to bare-metal management.

OpenStack Ironic provides bare-metal as a service. As a standalone service it can discover bare-metal nodes, catalog them in a management database, and manage the entire server lifecycle including enrolling, provisioning, maintenance, and decommissioning. When used as a driver to OpenStack Nova and combined with the full suite of OpenStack services, it delivers a powerful, cloud-like service for managing your entire bare-metal infrastructure.

This raises the question: How does one bootstrap OpenStack services to manage bare-metal infrastructure? One typical solution is to use the same container-based installation tools as described in the previous sections to create a seed installation. This seed, often called an ‘undercloud’, can be used to entirely automate the management of a bare-metal cluster as if it were a virtualized cloud.

This opens up an opportunity to not just run OpenStack virtualization on a bare-metal cloud, but to also run bare-metal Kubernetes-only installations that can take full advantage of the identity, storage, networking, and other cloud APIs available through OpenStack services.

Both infrastructure containers and bare-metal infrastructure are important, but when most people think of containers, they’re thinking of application containers. The isolation, encapsulation, and ease of maintenance offered by containers makes them an ideal solution for delivering applications. However, containers still need a host platform to serve them from, whether bare-metal, public cloud, or private cloud.

Kubernetes is a platform for delivering applications, and works best with cloud-APIs that can automate the delivery of critical infrastructure such as permanent storage, load-balancers, networks, and dynamic allocation of compute nodes. OpenStack delivers cloud infrastructure, whether as an on-prem private cloud or through any of the available public or managed OpenStack clouds.

OpenStack was one of the first upstream cloud providers for Kubernetes, with an active team of developers maintaining the "Kubernetes/Cloud Provider OpenStack" plugin. This plugin allows Kubernetes to take advantage of Cinder block storage, Neutron and Octavia Load Balancers, and direct management of compute resources with Nova. Using the provider is as simple as deploying the driver to your Kubernetes installation, setting a flag to load the driver, and providing your local user cloud credentials.

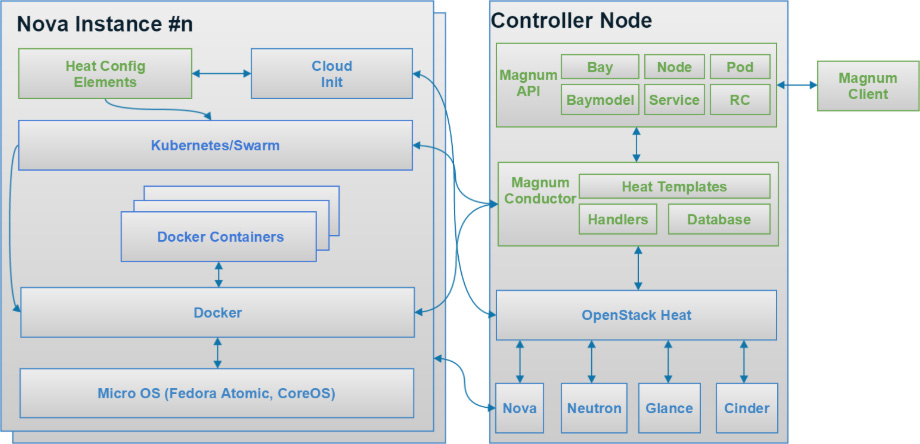

There are a number of solutions for installing Kubernetes and other application frameworks on top of OpenStack. One of the easiest ways to deliver container frameworks is to use Magnum, an OpenStack project that provides a simple API to deploy fully managed clusters backed by a choice of several application platforms, including Kubernetes. It’s an example of a Kubernetes deployment system that relies on OpenStack APIs and cloud provider plugin. For example, right now it’s being used to manage over 200 independent and federated Kubernetes installations on CERN’s OpenStack on-site cloud, as well as on partner clouds. If you don’t have the Magnum API available to you in your preferred OpenStack cloud, you can use any other Kubernetes installation tools such as the kubeadm, Kubernetes Anywhere, Cross-Cloud, or Kubespray, to install and manage your Kubernetes cluster on OpenStack. Because each uses standard Kubernetes, it’s easy to enable the cloud provider interface to take advantage of storage and load balancing.

Zun, another OpenStack project, offers a lighter-weight container service API for managing individual containers without the need for managing servers or clusters. An OpenStack-hosted Kubernetes cluster is elastic because it can be dynamically resized by adding or removing cloud resources to the cluster directly through the Nova API. Alternatively, Kubernetes can serve as a container backend to OpenStack Zun, turning over the management of the pod infrastructure to Zun. It offers a lighter-weight and multi-tenant container service API for running containers without the need for directly creating servers. Direct integration with Neutron and Cinder are used to provide networking and volumes for individual containers.

Finally, the Qinling project offers "Function as a Service" that aims to provide a platform to support serverless functions, similar to Lambda, Azure Functions, or Google Cloud Functions. It further abstracts the management of containers, and allows users to accelerate development with an event-driven, serverless compute experience that scales on demand. Qinling supports different container orchestration backends like Kubernetes and Docker swarm, a variety of popular function package storage backends like local storage and OpenStack Swift.

Kata Containers, a new open source project, is a novel implementation of a lightweight virtual machine that seamlessly integrates within the container ecosystem. Kata Containers are as light and fast as containers and integrate with the container management layers – including popular orchestration tools such as Docker and Kubernetes (k8s) – while also delivering the security advantages of VMs. Kata Containers adhere to the Open Container Initiative (OCI) standard, which the OpenStack Foundation is an active member of. Kata Containers is hosted at the OpenStack Foundation, but is a separate project from the OpenStack project with its own governance and community.

The industry shift to containers presents unique challenges in securing user workloads within multi-tenant environments with a mix of both trusted and untrusted workloads. Kata Containers uses hardware-backed isolation as the boundary for each container or collection of containers in a pod. This approach addresses the security concerns of a shared kernel in a traditional container architecture.

Kata Containers is an excellent fit for both on-demand, event-based deployments such as continuous integration/continuous delivery, as well as longer running web server applications. Kata also enables an easier transition to containers from traditional virtualized environments, as it supports legacy guest kernels and device pass through capabilities. Kata Containers deliver enhanced security, scalability and higher resource utilization, while at the same time leading to an overall simplified stack.

One of the primary benefits of choosing open source platforms is in the stability of interfaces across standard deployments of those platforms. Both the OpenStack Foundation and the Cloud Native Computing Foundation (CNCF) maintain interoperability standards for OpenStack clouds and Kubernetes clusters, guaranteeing that libraries, applications, and drivers will work across all platforms regardless of where they are deployed. This creates opportunities for side-by-side integrations, allowing both OpenStack and Kubernetes to take advantage of the resources provided by the other.

The OpenStack Special Interest Group (SIG-OpenStack) in the Kubernetes community maintains the Cloud Provider OpenStack plugin. In addition to cloud provider interface for running Kubernetes on OpenStack, it also maintains several drivers that allows Kubernetes to take advantage of individual OpenStack services. These drivers include:

Both OpenStack and Kubernetes support highly dynamic networking models that are backed by a variety of drivers. Because of these standard network interfaces, it’s easy to build standalone OpenStack and Kubernetes clusters with strong network integrations. Within OpenStack, the Kuryr project produces a Common Network Interface (CNI) driver that delivers Neutron networking to Docker and Kubernetes. On the flip side, there projects like Calico offer Neutron drivers, providing direct access to popular Kubernetes network overlays through standard Neutron APIs.

Many members of the OpenStack community are contributing new code to various OpenStack projects relevant to containers, evaluating the implications and benefits of containers, and using containers in production to solve challenges and unlock new capabilities. This section highlights some of the most interesting case studies.

AT&T, one of the largest telecommunications companies in the world, leverages container technology to deploy and manage OpenStack itself, relying on infrastructure containers to generate simplicity and efficiency, with the aim of building their 5G infrastructure on containerized OpenStack.

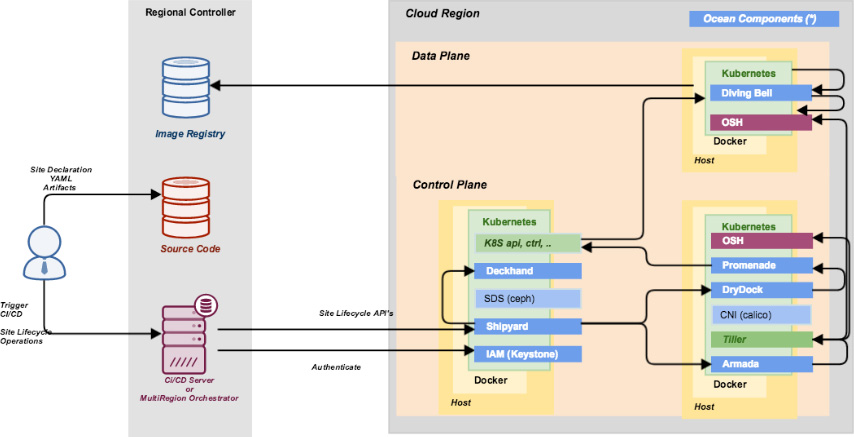

To accomplish their goals, AT&T is using the OpenStack-Helm project to orchestrate LOCI-based OpenStack images across a Kubernetes cluster, also leveraging Kubernetes, Docker, and the core OpenStack services. They’re also using Bandit, Tempest, Patrole, and many other OpenStack projects. AT&T is also collaborating in the community to introduce a collection of undercloud projects called Airship, which will provision clouds from bare-metal to production-grade Kubernetes running OpenStack workloads.

AT&T is finding that containerization allows them to shift traditional deployment-type activities far to the left, and to validate them using CI/CD. Kubernetes additionally provides massive scalability and resiliency, as well as hooks to allow OpenStack-Helm to declaratively configure operational behavior, inject configuration, and accomplish rolling upgrades and updates without impacting tenant workloads.

Leveraging container technology to deploy and manage OpenStack shouldn’t have much obvious impact on tenants — with the exception that they will have a more highly resilient platform, and will be able to get cloud features more frequently and with minimal interruption. AT&T’s operations teams new experience will shift more of their efforts to defining the declarative configuration for a site, and to let the Kubernetes-oriented automation carry out the deployments themselves.

AT&T aims to use this architecture to power the virtual network functions that form the backbone of its consumer and business-focused products and services. The initial use case for AT&T’s containerized Network Cloud will be the initial deployment of VNFs for the emerging 5G networking. OpenStack has been, is, and will be an excellent fit for AT&T’s VNF-focused cloud use cases. Containerization is simply an evolution that allows AT&T to deploy, manage, and scale their OpenStack infrastructure in a more reliable, rapid, zero-touch manner.

Operationally, AT&T is still testing this approach but has committed to getting 5G service into production before the end of the year. OpenStack and container technology will form the backbone of this service, which is strategically important for AT&T’s millions of users. Deploying their 5G service will demonstrate the relevance of OpenStack and containers in a massively distributed production environment.

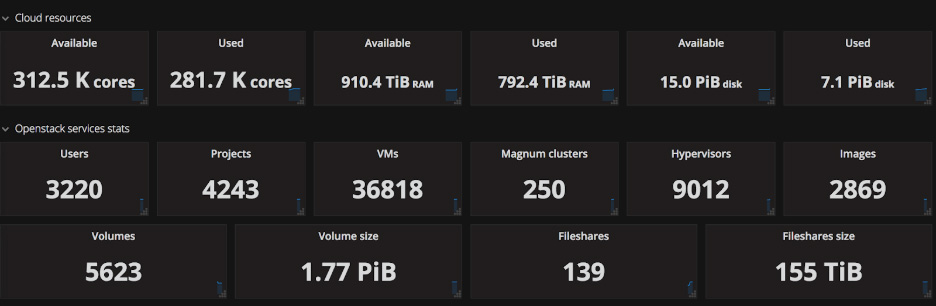

CERN, the European Organization for Nuclear Research, enables physicists and engineers to probe the fundamental structure of the universe, using the world’s largest and most complex scientific instruments to study the basic constituents of matter – the fundamental particles. The CERN cloud provides physicists with compute resources for scientific computing, analyzing data coming from the Large Hadron Collider and other experiments.

CERN has been running OpenStack in production since 2013 and is now providing services for virtual machines, bare-metal and containers within a single cloud. Containers run on either virtual machines or bare-metal depending on the use cases, all provisioned via OpenStack Magnum. A selection of different container technologies are available including Kubernetes, Docker Swarm and DC/OS.

CERN is currently running 250 container clusters provisioned through Magnum on top of OpenStack.

CERN’s OpenStack cloud gives users self-service access to request a configured container engine with a couple of commands or via a web GUI. This allows rapid utilization of the technologies and can scale to 1000s of nodes if needed. Best practice configurations are available with built in monitoring and integration into CERN storage and authentication services.

Running this resource pool efficiently, scaling it without needing extra operations manpower requires consistent management processes and tools. Adding containers via Magnum on top of OpenStack enabled the service to use the automation previously developed, such as hardware repair processes and consistent authorisation models while supporting rapidly reallocation of resources depending on user needs.

As a publicly funded laboratory, open source solutions such as Kubernetes and OpenStack provide a framework to collaborate with other organisations and give back to the communities. CERN has worked with a number of vendors through the CERN openlab framework, such as Rackspace and Huawei, to provide clouds at scale with functionalities like Magnum and federation. These experiences are also shared through OpenStack Special Interest Groups, with other sciences such as the Square Kilometer Array (SKA), public presentations such as Kubecon Europe and blogs such as the OpenStack in Production.

At CERN, several workloads run within containers provisioned by Magnum, these include:

Integrating virtual machines, container engines and bare-metal under a single framework provides for easy views on usage accounting, ownership and quota. Manila storage drivers for Kubernetes allow transparent provisioning of file shares. This supports both the IT department in capacity planning and the experiment resource coordinators in defining the priorities for their working groups. Resource management policies such as reassignment or expiry of resources on departure of staff are handled in consistent workflows.

SK Telecom (SKT), South Korea’s largest telecommunications operator, has been exploring optimized approaches for deploying OpenStack on Kubernetes with the aim of putting core business functions on containerized OpenStack by the end of 2018. SKT leverages Kolla and Openstack-Helm. with deployments automated by Kubespray. SKT devotes nearly 100% of it’s development efforts to OpenStack-Helm, and works closely with AT&T to make OpenStack-Helm successful.

SKT has also incorporated other tools into their OpenStack on Kubernetes efforts. For logging, monitoring, and alarms, they are using Prometheus and Elasticsearch, Fluent-bit, and Kibana, all of which are default reference tools in the OpenStack-Helm community. SKT combines all of these into a single closed-integrated solution called TACO: SKT All Container OpenStack.

SKT specifically emphasizes an automated continuous integration/continuous delivery (CI/CD) pipeline around containerized Openstack on Kubernetes. SKT’s CI system consists of Jenkins, Rally, Tempest, Docker Registry, as well as Jira and Bitbucket. SKT also developed an open source tool called Cookiemonster, a chaos-monkey like resiliency test tool for Kubernetes deployment that performs resiliency tests for their CI pipeline.

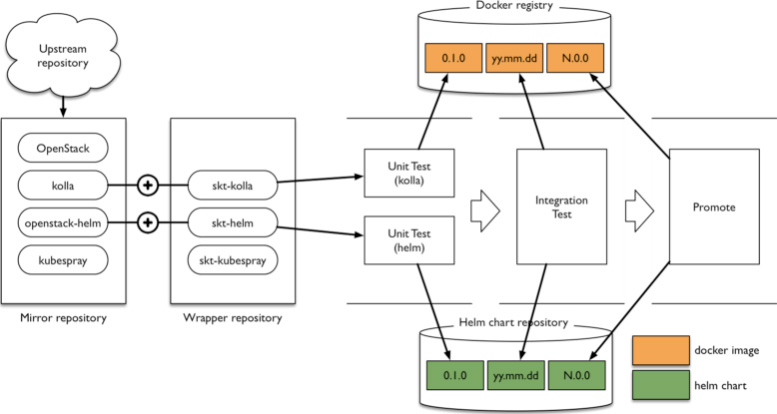

With every change, SKT automatically builds and tests both the OpenStack containers and Helm charts. Daily, they automatically install a highly available OpenStack deployment with three control nodes and two compute-nodes, run 400 test cases from Tempest against it to validate the services, and finally run resiliency testing with Cookiemonster and Rally. The complete CI system is illustrated in the following diagram:

SKT automates its deployments with Armada, a sub-project of Airship, which was introduced in the community as a new open infrastructure project by AT&T. SKT is collaborating in community to provide enhancements to the project based on their production uses.

In practical use, SKT has already seen a large number of benefits from deploying OpenStack on Kubernetes including:

SKT is still testing the approach, but is actively moving towards running their OpenStack-Helm deployments in production. By end of this year, SKT will have at least three production clusters, with the fourth and largest coming online in 2019. These use cases include:

SKT is also trying to improve automation on telecom infrastructure operation by utilizing containerized VNFs and leveraging containers’ auto healing and fast scale-out features. In order to allow interaction between virtual machine based VNFs and containerized VNFs, Simplified Overlay Network Architecture (SONA), which is a virtual network solution for OpenStack, will support communication between VMs and containers. SONA uses the Kuryr project for integration of OpenStack and Kubernetes, and it optimizes network performance using software defined networking technologies.

Overall, SKT is finding that Kubernetes helps solve many of the complexities of deploying and operating OpenStack. Simplifying OpenStack gives them a powerful approach to deliver advanced infrastructure innovation for the 5G era. Focusing efforts on Openstack on Kubernetes dramatically increased their internal capability to deal with the evolving shift toward microservices in containers and become a critical infrastructure for delivering Artificial Intelligence, Internet of Things, and Machine Learning.

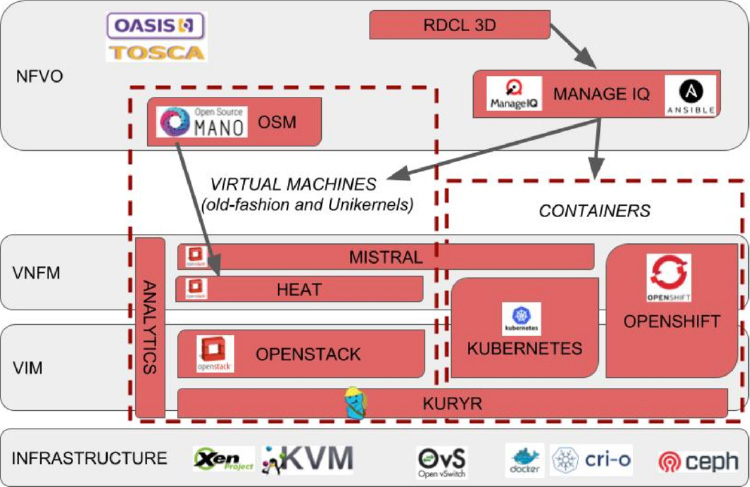

The Superfluidity project is made up of 18 partners from 12 European countries. It aims to enhance the ability to instantiate services on-the-fly, run them anywhere in the network (core, aggregation, edge) and shift them transparently to different locations. SUPERFLUIDITY is a European Research project (Horizon 2020) trying to build the basic infrastructure blocks for 5G networks by leveraging and extending well known open source projects. SUPERFLUIDITY will provide a converged cloud-based 5G concept that will enable innovative use cases in the mobile edge, empower new business models, and reduce investment and operational costs.

To pursue these goals, the project consortium is shifting away from legacy, VM-based applications to Cloud Native containerized applications. Kuryr serves as a bridge between OpenStack virtual machines, and Kubernetes and OpenShift containerized services.

The project makes use of ManageIQ as a central networks function virtualization orchestrator (NFVO), Ansible for Application deployment and lifecycle management, OpenStack services including Heat, Neutron, and Octavia, and Kubernetes through OpenShift for VMs and containers integration.

By leveraging Ansible playbooks executed from the ManageIQ appliance, SUPERFLUIDITY offers a common way to deploy applications. These applications in turn use the cloud orchestration functionality provided by OpenStack Heat templates and OpenShift templates.

The consortium deploys 5G cloud radio access networks (CRAN) and mobile edge computing (MEC) components within containers. It also deploys high throughput applications like video streaming on top of the distributed infrastructure.

Shifting toward a cloud native approach to application delivery allows for rapid and resilient SUPERFLUIDITY installations. It enables a smooth transition from VM-based applications and components to containers, while retaining the versatility to enable VMs for some specific applications. Examples of these applications are special security protections or network acceleration required by single-route input/output virtualization (SRIOV).

In scale performance testing, SUPERFLUIDITY was able to launch approximately 1000 pods at a rate of 22 pods/second (with time measured from creation to running). This remarkable performance was achieved by running OpenShift on VMs managed by OpenStack, with Kuryr acting as a pod network driver to avoid double-encapsulation performance hits.

Over the past few years, as containers have become an important tool for developers and organizations alike, OpenStack has leveraged its modular design and expansive community to integrate container technologies at many levels. This can be seen both by the various organizations bringing containers and OpenStack into production, and the number of projects that work alongside containers to deliver new capabilities. The OpenStack Foundation is committed to ensuring that emerging technologies can be incorporated and utilized within OpenStack, and containers are an important example of that commitment.

To learn more, visit the Containers Landing Page , where you can find a copy of this document as well as links to dozens of videos focused on the integrations of OpenStack and containers. Kubernetes SIG-OpenStack has a Slack channel, mailing list, and weekly meeting if you engage directly with the community that’s building Kubernetes and OpenStack integrations.